At the United Nations General Assembly in New York, Kenyan President William Ruto reiterated the country’s commitment to support Haiti with a multinational force that will fight gang-related violence.

“Haiti is the ultimate test of international solidarity and collective action,” Ruto said on Thursday, adding that “the international community has failed this test so far and thus let down a people very, very badly.”

In August, some nations supported Kenya’s initiative to send police to Haiti, but others expressed uncertainty. A resolution is in the works so that the U.N. Security Council could authorize the move.

Ruto urged the U.N. to approve the resolution for Kenya’s mission, saying that the international body should “urgently deliver an appropriate framework to facilitate the deployment of multinational security support as part of a holistic response to Haiti’s challenges.”

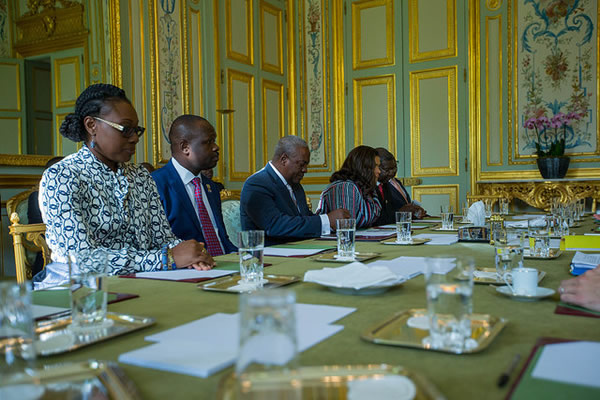

The two countries established diplomatic relations Wednesday.

Haitian Prime Minister Ariel Henry last year asked the United Nations to send a “specialized armed force from abroad.” Henry, installed as prime minister following the July 2021 assassination of President Jovenel Moise, made the call as gang violence surged in the country.

More than 200 powerful gangs have now taken control of much of the country, carrying out near-daily killings and kidnappings and causing tens of thousands of Haitians to flee their homes.

Close to 200,000 people have been internally displaced in Haiti, according to recent United Nations estimates.

Kenya’s offer to deploy a contingent of 1,000 police officers as part of a U.N.-backed multinational force comes as Haiti’s national police have struggled to control the gangs because of limited resources and chronic understaffing.

The offer, welcomed by Henry’s government, the U.N., Canada and the United States, has civil society groups expressing concern, pointing to the Kenyan police force’s own human rights record at home.

Irungu Houghton, executive director of Amnesty International Kenya, says while it would be an act of Pan-African solidarity for Nairobi to help bring stability to Haiti, he doubts Kenyan police would do anything to de-escalate the situation within the rule of law — primarily because of allegations of brutality by Kenyan police.

“We’ve had three months of about nine rounds of protests — each of them more violent than the last. We have documented no less than 40 deaths and over 100 injuries,” Houghton told VOA English to Africa’s TV program Straight Talk Africa.

“Some of those from people who are either recovering from being shot with live bullets or rubber bullets, or who have been brutally assaulted with batons,” he added.

Houghton says Haiti needs effective policing strategies built around trust between police and communities that establish “a sense of credibility around the rule of law.”

He believes Kenya’s police “simply are not at that level yet.”

The Kenya Police Service did not immediately respond to VOA’s request for comment shortly after the announcement.

David Monda, professor of political science at the City University of New York, said “while Kenyan police may not have covered themselves in glory with their actions in Kenya, every major police department has its challenges.”

Monda believes any police force deployed to Haiti would have challenges on the ground and within its own ranks.

Johanna LeBlanc, an attorney with Washington-based firm Adomi Advisory Group and a former policy adviser to the Haitian government, says Haiti’s troubled history with past foreign interventions, led by the U.S. and the U.N., gives pause to Haitian communities and rights groups.

“Human rights groups in Haiti do not want this to be another intervention with a Black face,” LeBlanc told VOA.

LeBlanc referred to the U.N.’s 2004-17 peacekeeping mission marred by allegations of sexual assault by its troops and staffers.

A 2019 report into the allegations implicated peacekeepers from 13 countries in multiple cases of sexual misconduct and rape during the U.N.’s 13-year mission to stabilize Haiti, known as MINUSTAH.

U.N. peacekeepers were also blamed for bringing cholera to Haiti in 2010, triggering an outbreak that killed thousands. The U.N. has admitted to playing a role in Haiti’s cholera epidemic but has not specifically acknowledged it introduced the disease.

“Parameters need to be set by the Haitian government, which I have not seen. But if you are going to accept help from another nation to address the insecurity challenges, we need to know how long will they stay in Haiti, and what the consequences are for human rights violations,” LeBlanc said.

Monda warned that intervention for intervention’s sake could be problematic.

He said what Haiti needs is an interim regime that is “broadly accepted” by the Haitian people, before any foreign intervention is considered.

A Kenyan-led deployment to Haiti still requires a mandate from the United Nations Security Council, as well as a formal agreement by local authorities. The council previously asked Secretary-General Antonio Guterres to present “a full range” report on possible options for Haiti, including a U.N.-led mission.

“Inaction is no longer an option,” Ruto said Thursday in an address at the U.N. “Haiti deserves better from the world. The cry of our brothers and sisters, who were the first people to win their struggle for freedom from colonial tyranny, has reached our ears and touched our hearts. Doing nothing in the face of the historic isolation, neglect and betrayal of the people of Haiti is out of question,” he said.

This story originated in VOA’s English to Africa Service. Salem Solomon contributed to this report.

Source: voanews.com