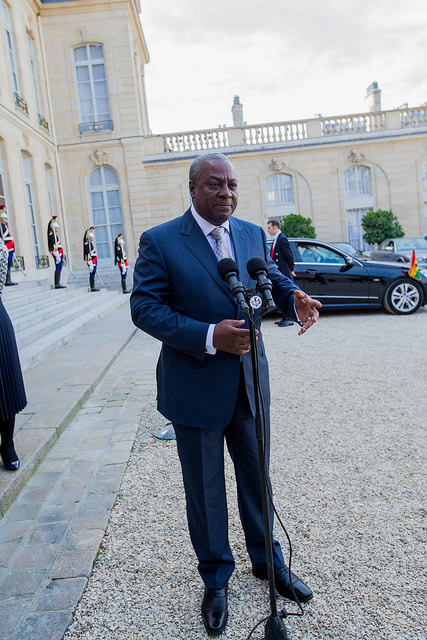

President Mahama addressing the 69th UN General Assembly in New York

President John Dramani Mahama today, addressed the 69th United Nations General Assembly in New York. President Mahama, who is also the Chair of the Economic Community of West African State (ECOWAS) called on the world to see Ebola not as “…. a Liberian problem, or a Sierra Leonean or Guinean problem. It is not just a West African problem. Ebola is a problem that belongs to the world because it is a disease that knows no boundaries”.

Below is the president full speech

Mr. President,

Mr. Secretary-General,

Distinguished Colleagues,

Ladies and Gentlemen,

Change has become an overriding theme in the language of today’s social and

political landscape. We speak of the need to change behaviours, attitudes, and

laws. We speak of the need to effect change in the areas of human rights and

social justice, in education and health administration.

We have come to understand the concept of change as a constant in our lives as

human beings and as citizens of this world. But does change automatically signify

progress?

There is an old saying with which I’m sure you are all familiar. It is, “the more

things change, the more they stay the same.”

Sometimes when I find myself listening to reports of the many recent

developments taking place in the world, that saying comes to mind, and I am

overcome with a strong sense of déjà vu- as though we have been here before.

When I hear reports about the taking of hostages and the savagery of

beheadings, it is 2004 again and week after week, there is news of the killing of

foreign hostages in Iraq.

When I hear reports about Israel and Gaza, it is 2005 again and Israel has

launched Operation Summer Rain, immediately followed by Operation Autumn

Clouds. The resulting death toll in the Gaza Strip is in the hundreds. Many are

children.

Likewise, reports of police brutality in the United States against an unarmed

black man takes me back to 1999 when 23-year old Guinean-born Amadou Diallo

was shot 19 times by four New York City police officers. Or to 1991 when Rodney

King was brutally beaten by five Los Angeles police officers. Both of those

incidents caused a tremendous public outcry, as has this year’s shooting to death

of 18-year old Michael Brown in Ferguson, Missouri, with the singular message of

“no justice, no peace.”

Mr. President,

Do such events indicate an outright regression? Does the uncomfortable

familiarity of some current world events mean that despite the changes so many

individuals and organizations have worked to achieve, we have made little or no

progress?

I would like to believe this is not so. I would like to believe these events of recent

times are merely setbacks that will motivate us to find more sustainable solutions,

slight reversals on that sinuous path toward true progress.

Dag Hammarskjöld, who served as the second Secretary-General of the United

Nations from 1953 until his untimely death in a plane crash in 1961 said, “the

pursuit of peace and progress cannot end in a few years in either victory or

defeat. The pursuit of peace and progress, with its trials and its errors, its

successes and its setbacks, can never be relaxed and never abandoned.”

In the course of the past several months, since the beginning of the Ebola

outbreak in West Africa, I have been reminded of both the importance and the

practicality of those words. True progress relies on neither victory nor defeat but

on persistence, on perseverance.

On 15th September, in my capacity as the Chair of ECOWAS, the Economic

Community of West African States, I travelled to Liberia, Sierra Leone and

Guinea. They are the three countries that have been most affected by the

outbreak of Ebola. These are nations that were recovering from conflict, civil wars

in Liberia and Sierra Leone that also adversely affected Guinea, which shares

borders with both countries.

These are nations that were struggling to rebuild their social and economic

infrastructures. Even before the outbreak of Ebola, these countries were already

operating with limited resources, with an insufficient number of treatment

facilities and a shortage of qualified medical staff.

So far, there have been five thousand, eight hundred and forty-three (5,843)

recorded cases of Ebola, including two thousand, eight hundred and three

(2,803) deaths.

The World Health Organization predicts that if the disease is not brought under

control, the number of cases could easily rise to 20,000 by as early as November.

What makes Ebola so dangerous is that the virus dares us to compromise the

impulses that exist at the very core of our humanity: our impulse to comfort one

another with love; to care for each other with the healing power of touch; and, to

maintain the dignity of our loved ones even in death with a public funeral and

properly marked grave.

Mr. President,

Ebola is a disease of isolation. It leaves family members afraid to embrace one

another, healthcare workers afraid to attend to patients, and it forces the living to

abandon the cultural rites of washing, embalming and burying their dead.

Instead they are zipped into a secure body bag, carried on a stretcher by

makeshift pallbearers in protective wear, then tossed into a freshly dug grave.

Just as individuals with Ebola are often shunned and ostracised by their

communities, the initial slowness of response by the international community, in

many ways, left the affected countries to suffer their fate alone.

In my travels to those three countries, despite my awareness of the suspension of

flights by some airlines, I was shocked to find the airports completely vacant.

Ebola is not just a Liberian problem, or a Sierra Leonean or Guinean problem. It

is not just a West African problem. Ebola is a problem that belongs to the world

because it is a disease that knows no boundaries.

We cannot afford to let fear keep us away. We cannot afford to let it compromise

the very impulses that not only define but retain our humanity. We must erase

the stigma. To that end, Ghana has offered the use of its capital city, Accra, as a

base of operations for activities geared towards the containment of the disease.

I would like to commend UN Secretary-General Ban-Ki Moon and the Security

Council for establishing the United Nations Mission for Ebola Emergency

Response (UNMEER). I would also like to acknowledge and commend President

Barack Obama and the people of the United States of America for their

enormous commitment to the fight against Ebola.

Health officials have announced numerous times that, in theory, it is relatively

easy to stop the spread of Ebola because it is transmitted through contact with

bodily fluids. It has been suggested that through changes in behaviour and

practices, the public could potentially reduce, if not eliminate, their exposure to

the virus. Yet, in reality, the Ebola virus was able to spread so quickly throughout

the West African sub region because of its exposure to the fluidity of our

borders.

The free movement of people, goods and services throughout the West African

sub region is something that ECOWAS has been promoting for the last several

decades. It allows interaction and increased trade between our fifteen member

states. However, without the proper preventive measures in place, such fluidity

can also enable the free movement of disease, drugs, arms, human traffickers

and terrorists.

Mr. President,

Unfortunately, Africa is especially vulnerable to terrorism. Because of its sheer

size and vast terrain it offers myriad places for terrorists to hide and create safe

havens. With over 60% of Africa’s population under the age of thirty-five and a

significant number living in extreme poverty, terrorists also have the opportunity

to recruit new members by exploiting the ignorance and disillusionment of

young people who lack the skills, education and opportunities to find gainful

employment.

The proliferation of technology has made even the most remote areas of the

continent accessible with a single phone call or keystroke. What this does is

facilitate communication within terrorist cells and between terrorist organizations.

It would now be far too simplistic, not to mention myopic, for a nation to believe

that they are just dealing with any one terrorist organization, such as Boko

Haram, Al-Shabaab, Ansar al Dine, Al-Qaeda, Hezbollah, the Taliban, ISIS or the

Khorasan group.

Because of the assistance and cooperation that exists between them, they have

in fact become several tentacles of a single organism. So, too, must we come

together as one cohesive body, united in our battle to defend our freedoms and

values. We, too, must communicate within and between ourselves; we must

cooperate, lend assistance and resources to fight and conquer this common

threat.

Mr. President,

Since the start of the global recession, economic growth rates have generally

declined and people have, by and large, become pessimistic about their future.

This month, the Pew Research Center published the results of a 44-country

survey conducted in Spring 2014 to assess public views of major economic

changes in the world. According to these results, a global median of 69% are not

pleased with the way things are going in their countries. This includes advanced,

as well as developing economies. The concerns expressed cut across a wide

spectrum of issues, such as inflation, unemployment, income inequality and

public debt.

My country, Ghana is no exception. Over the last year, the public has seen an

increase in the cost of living. Falling commodity prices led not only to a fall in tax

revenue from companies that operate in Ghana, but they also led to a massive

decline in export earnings. This contributed to a general sense of macro-

economic instability and placed a great deal of pressure on our currency, the

cedi.

For the past 22 years, Ghanaians have witnessed a steady improvement in the

circumstances of our nation. With a return to democracy and the rule of law, six

successful elections and peaceful transitions of power, Ghana became an

example for other African nations turning toward democracy and constitutional

rule. The stability inspired investor confidence and increased growth. Soon

Ghana was deemed one of the fastest growing economies in the world.

This did not make us immune to the economic challenges that were facing many

nations across the globe. Quite the opposite. Instability in the global commodity

markets have a direct bearing on our budgets and, hence, our ability to finance

our development.

The global downturn exposed the weaknesses in our foundation. It alerted us to

the need for change, the need to establish the proper institutions for effective

economic management, institutions that will foster resilience and an ability to

better absorb the blows of unexpected occurrences or outcomes.

The anxieties and concerns of the Ghanaian public are understandable.

Like so many African countries, Ghana has been through dark economic times,

and our seemingly changing fortunes, with its uncomfortable familiarity, brought

on a fear of regression. But this was merely a setback, a slight reversal.

Already, the home grown measures of fiscal stabilization that we have taken are

yielding results. Only this month, Ghana surprised even its most ardent critics

when it launched its third Eurobond for an amount of one (1) billion dollars. This

successful floatation represents a return of investor confidence in the prospects

of the Ghanaian economy. This confidence is apparent in the recent rebound of

the Cedi. Over the last two weeks, the Cedi has appreciated significantly against

its major trading currencies.

Last year when I addressed this august Assembly, I explained that it is not

sympathy we want; it is partnership, the ability to stand on our own feet. In an

attempt to establish such a partnership, we have entered into discussions with

the IMF, an organization that is no stranger to the process of self-assessment and

the implementation of change in the pursuit of true progress.

Indeed, both Ghana and the IMF have evolved, and this partnership has the

potential to bring about the sort of transformation that will move Ghana from the

ranks of low middle-income into a full-fledged middle-income status.

Mr. President,

The coming year will mark the 20th anniversary of the World Conference on

Women that was held in Beijing in 1995. I would like to note, with great pride,

that it will also mark the 40th anniversary of Ghana’s establishment of the National

Council on Women and Development, which has since been renamed the

Department of Gender.

Ghana has a long-held commitment to the betterment of women’s lives, and my

administration has made it a priority to carry on this tradition. In fact, much, if not

all, of what we are doing falls directly in line with the areas of concern

enumerated in the Beijing Platform for Action.

This administration boasts the highest number of women appointed to public

office in the history of Ghana. Seven of our Cabinet Ministers are women, as are

the holders of several senior public service posts- and I hope the fact that they

are too numerous to list is an indication that we are reaching toward the ideal.

We have submitted to Parliament an Intestate Succession Bill, which ensures that

if a spouse dies without having written a will, the surviving spouse will not be

dispossessed of their marital assets. Also submitted to Parliament is a Property

Rights of Spouses Bill, which ensures that spouses are entitled to fair portions of

property acquired during the union.

Also in existence are several other pieces of legislation designed to offer

protection and empowerment of women such as the Domestic Violence Act, the

Human Trafficking Act, an Affirmative Action Bill, and a Gender Policy.

Mr. President,

I spoke earlier of isolation. Very few nations have experienced the sort of

exclusion that Cuba has for the last several decades suffered as a result of the

U.S. embargo on that country. Ghana stands firm on its position that the

embargo should be lifted.

Also, Ghana calls for a halt to the establishment of settlements in Palestinian

territories. We have consistently expressed our support of a two-state solution for

the Israeli-Palestinian struggle, with the nations co-existing peacefully.

Mr. President,

This year, the world’s attention has been drawn to the urgency of addressing the

growing problem of inequality and the threats that it poses to our unrelenting

pursuit of peace. I would like to also draw attention to the pervasive presence of

religious intolerance.

At the root of all of the world’s major religions exists the call for compassion,

forgiveness, tolerance, peace, and love. Nevertheless, the use of religious

dogma and extremism as a weapon of violence persists.

In this age of terrorism and political turmoil; national, regional and ethnic

conflict, it may be tempting to use the actions of a few to justify prejudice toward

many. It may be tempting to combine the faithful with the fanatical.

But those of us who envision a just and peaceful world cannot and should not

yield to those temptations. Time and time again, history has shown us that the

changing of a world begins with the power that rests in the hands of people,

ordinary individuals.

Or, in the words of one of the greatest teachers and leaders of nonviolence,

Mahatma Gandhi, “You must be the change you wish to see in the world.”

Today our Jewish brothers and sisters are celebrating Rosh Hashanah, their New

Year. To them, I say, “L’Ashana Tova.”

Next week, our Muslim brothers and sisters will be celebrating Eid-al-Adha,

Festival of the Sacrifice. To them, I say, “Eid Mubarrak.”

And, to you, Mr. President, I say, “Many thanks for the opportunity, and for your

kind attention.”

May God bless us all.