The Nobel Committee praised Prime Minister Abiy Ahmed’s peace initiatives

Nobel Peace Prize winner Abiy Ahmed has shaken up Ethiopia since becoming prime minister in April last year, but what ideas are guiding the man who has received the prize in Oslo? The BBC’s Kalkidan Yibeltal in Addis Ababa has been reading the book that outlines his philosophy.

Medemer has become a buzzword in Ethiopia.

The Amharic language term which literally means “addition”, but is also translated as “coming together”, sums up what Prime Minister Abiy sees as a uniquely Ethiopian approach to dealing with the country’s challenges.

And it has become hard to escape after the prime minister’s book of the same name was launched in lavish ceremonies across Ethiopia in October, with a reported hundreds of thousands of copies printed in the country’s two most widely spoken languages – Amharic and Afaan Oromoo.

Across 16 chapters and 280 pages he outlines his vision, which he says he has been nurturing since childhood.

Mr Abiy wants to foster a sense of national unity in the face of ethnic divisions, but also wants to celebrate that diversity. His success in walking this tight-rope will define his time in power.

What is the essence of medemer?

At the heart of the philosophy is the conviction that different, and even contrary, views can be brought together and a compromise can be found. It is also a rejection of dogmatism.

Since taking office, Mr Abiy has clearly departed from the way the country was governed for most of the last three decades.

He has broken from the hard-line security state to encourage a more liberal approach to politics.

He has also said that his predecessors’ attempts to apply Marxist and statist approaches to economic development failed because they were alien to Ethiopia.

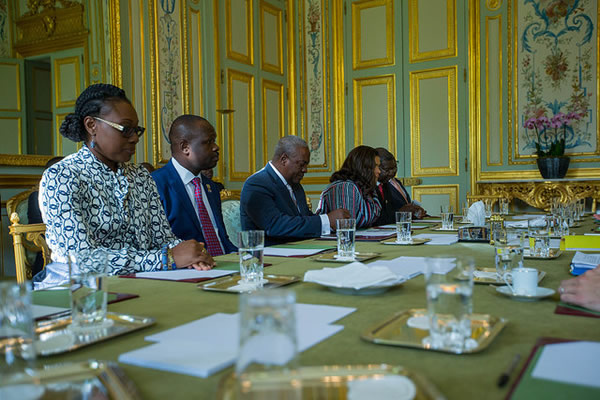

The Nobel Peace Prize announcement was big news in Ethiopia in October

“We need a sovereign and Ethiopian philosophy that stems from Ethiopians’ basic character, that can solve our problems… that can connect all of us,” he writes in Medemer.

He argues that Ethiopian culture values inclusion and cooperation.

Critics say that while this might sound good, it does not offer a practical way forward or a guide about how that compromise can be found.

In April, political analyst Hilina Berhanu said that while medemer was easily understandable and “served as a painkiller” for what went before, it lacks the complexity needed to map out the future.

Why has Abiy developed this idea?

Mr Abiy began talking about medemer long before he became prime minister.

Serving in senior government positions, he used the term while telling his colleagues the importance of bringing extreme opinions together and encouraging people to work in harmony.

As prime minister he has said medemer can cure many of the woes ailing Africa’s second most populous country, from poverty to deadly ethnic conflicts.

He has urged people to come together under a shared vision rather than be trapped by a history of ethnic and political division. Otherwise, he has warned, the very existence of the state could be brought into question.

What does it say about ethnicity in Ethiopia?

It is somewhat ironic that while the prime minister has spoken about unity, his political reforms have lifted the lid on simmering ethnic tensions in the country.

In the past 20 months, ethnic violence has claimed the lives of thousands of people and forced millions of others from their homes.

Ethiopia’s federal constitution, introduced in 1995, created ethnically based states. The arrangement puts a disproportionate emphasis on ethnic identity and ignores other forms of identity like gender and economic class, Mr Abiy says.

But he also recognises that historical injustices against some ethnic groups could be behind the increased tensions.

In fact, the prime minister, who is from the Oromo ethnic group, came to power on the back of a wave of protests from the Oromo community, who had complained of economic and political marginalisation.

Nevertheless, medemer calls for ethnic groups to voluntarily come together in a union that celebrates and promotes diversity. Mr Abiy argues that ethnic nationalism can go hand in hand with what he calls “civic nationalism”, which focuses on individual rights.

How this can happen practically is harder to see.

But in recent months, the prime minister has spearheaded the transformation of the country’s ethnically based governing coalition into a single party. In a sign of how hard medemer might be to achieve in practise, this move was immediately rejected by some groups.

Are people convinced?

In October, in a vivid sign that not everyone buys into Mr Abiy’s vision for Ethiopia, some protesters burnt copies of his book, shouting “down, down, medemer”.

These were young Oromos, who feared that their interests could be ignored once again if national unity is promoted at the expense of ethnic interests.

The leadership of the once-dominant Tigrayan People’s Liberation Front (TPLF) have described the prime minister’s philosophy as indistinct. The TPLF has refused to join Mr Abiy’s new merged party.

However, Mr Abiy is convinced it will help the country flourish and many supporters say it will build bridges in a country that is deeply divided along ethnic and religious lines.

Source: BBC