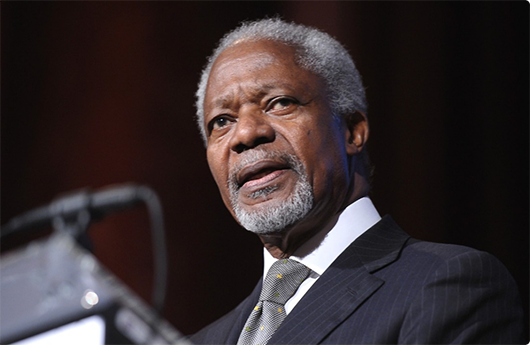

Kofi Annan

Former UN Secretary General

Ladies and Gentlemen, let me start by saying how pleased I am to be with you today.

I want to thank the Economist Group both for my invitation and, more importantly, for bringing together so many leading figures in this field.

From long experience, I know how expert gatherings like this can be catalysts for the development of innovative solutions and partnerships.

And, as this audience understands, there are few issues where such fresh thinking and energy is more needed than the global priority and resources given to depression.

Let us be honest. Sometimes the title of a conference can overstate challenges in an understandable attempt to focus attention on a neglected issue.

But that is not the case today. Calling the challenge of depression a global crisis is no exaggeration at all.

This is, after all, a condition from which almost seven per cent of the world’s population – around 400 million people – suffers.

It is both disabling for those afflicted and can place enormous burdens on their families.

It robs economies of people’s energy and talents at the same time as adding hugely to the costs on the public purse.

Depression, directly and indirectly, was estimated in 2010 to have a global cost of at least US$ 800 billion, a sum expected to more than double over the next 20 years.

All this explains why depression is, the WHO has said, already the leading cause of disability in the world.

It is also predicted soon to move from fourth to second place in contributing to the overall global burden of disease.

There is one further cause for concern. Women are twice as likely to suffer from depression as men.

With maternal mental health a substantial influence on growth during childhood, depression can cast its shadow from one generation to the next.

It is why I hope this conference can begin the process of pushing depression up the global agenda.

Ladies and gentlemen, in preparing some opening remarks for today, I was well aware that I lack medical, let alone psychiatric, expertise.

Reading up on the distinguished achievements of those speaking and attending today, I know this knowledge is not in short supply.

So I will leave discussion on these areas to those far more qualified than myself.

But the truth is, of course, it is not lack of medical knowledge that is at the heart of the world’s collective failure to tackle depression.

After all, there is an increasing understanding both of the condition and of how it can be treated.

Our difficulties rest more on a lack of political resolve.

There has been a failure to acknowledge the scale of the problem and to put in place the policies and resources to overcome it.

The fight against depression has fallen victim to the worrying tendency to focus on the short-term rather than long-term underlying challenges.

There has also been a lack of understanding of its links with other serious global problems and how the failure to tackle depression undermines the fundamental human rights of hundreds of millions of people.

This begins, of course, with the denial of even the most basic levels of the treatment and support.

The WHO has rightly stressed how important good mental health is for our individual and collective well-being.

Yet even in richer, more developed countries, help for those with depression can lag badly behind those suffering from many physical conditions.

In less developed countries without a proper functioning health system, such support and treatment can be non-existent.

But it is, of course, the nature of depression that it is these same countries where its prevalence and severity is greatest.

The stress and despair caused by natural disasters, conflict or abject poverty, for example, all too often leads to higher rates of depression.

But lack of treatment and support is not the only denial of rights that those with depression suffer.

Too often and in too many societies, those with mental health problems face discrimination and isolation.

So we have to tackle the lack of resources and trained providers which prevent effective and universal care.

But we also have to deal with social stigma and lack of community understanding associated with mental disorders.

This is all the more shocking given that depression can affect all of us.

Indeed, there will hardly be an extended family where one member has not suffered from its impact.

Ladies and gentlemen, so this is the background to our discussions today.

But there is a more positive side to the picture.

As I have said, we know more than ever about the condition.

Diagnostic criteria and screening mechanisms are now well-established.

There are an increasing number of simple, effective psychological and pharmaceutical interventions.

Economic analysis has also shown indicated that treating depression in primary care is feasible, affordable and cost-effective.

We also have a great deal more understanding of the prevention strategies which can help avert depression before it takes root.

The challenge is to find the global vision and leadership to maximise the benefits for individuals, families, communities and countries.

How we do this will, I am sure, be a major part of our discussion today.

But let me, from my experience, set out a few initial ideas.

First, as the world is thinking about a development framework to build on the Millennium Development Goals, we need to place mental health in general and depression in particular within the post-2015 agenda.

It is, of course, again human nature to focus on the MDGs which won’t be reached and critical to keep up the pressure to close the gap as quickly as possible.

But this should not detract from the remarkable progress that has been achieved thanks to the global commitment and focus the MDGs brought to some of the world’s greatest challenges.

By ensuring mental health and depression is not forgotten when the post 2015 development agenda is drawn up, we can have the same positive impact.

There is no doubt that depression must become a global priority because it not only affects health and well-being but also diminishes labour productivity and economic growth.

Without tackling it, our wider ambitions for the world will be much harder to achieve.

As a first step, I note that WHO member states have already approved the 2013-2020 mental health action plan.

This calls for a 20% increase in treatment for mental health including depression by 2020.

We must ensure these commitments are turned in concrete action on the ground in every country.

Second, we need to find ways to widen the numbers of patients receiving treatment for depression.

This is not just a matter of insufficient resources but also of a failure to integrate its assessment and management into general health care.

This requires improved education of general medical and health staff about depression both in initial professional training and through refresher courses.

We have to find ways, at a time of increased pressure on budgets, to improve health and social services for those suffering from depression.

Solutions must also include enhanced legal, social and financial protection for individuals, families and communities adversely affected by depression and its consequences.

More widely, we need to find ways to provide better information on depression, more awareness and education at grassroots level.

Third, the MDGs and success of initiatives to tackle infectious diseases has shown the immense value of building innovative partnerships across sectors and countries.

None of us have a monopoly of wisdom.

Throughout my career, I have found that the more people, organisations and sectors we can involve in finding solutions and increasing resources, the greater and faster the results will be.

I appeal to you to cast your net wide when forging new alliances.

Depression, like any public health problem, has many impacts and dimensions.

The danger is that this can make it harder to shape a coherent and effective response.

There is a desperate need to bring together countries, governments, academic institutions, the private sector, charitable foundations and civil society.

We need the widest possible partnerships and collective resources to overcome this challenge.

Ladies and gentlemen, it is a big agenda. I don’t underestimate the scale of the challenge.

But I have also seen how through commitment and partnership, progress can be delivered in the most testing of circumstances.

Increasingly, we have the knowledge about depression to make a difference.

We now need to find the will and resources to use this knowledge to transform the lives of hundreds of millions of people. Thank you.

By Kofi Annan

Former UN Secretary General