Polls opened on Thursday in Madagascar’s presidential election, which is being boycotted by most opposition candidates over concerns about the vote’s integrity.

The Indian Ocean island nation is the leading global producer of vanilla but one of the world’s poorest countries, and has been shaken by successive political crises since independence from France in 1960.

President Andry Rajoelina has brushed off criticism and expressed confidence that he will secure re-election in the first round of voting.

Following a nighttime curfew and weeks of protests, voting got calmly under way on Thursday morning, according to journalists, with polls set to close at 05:00 pm (1400 GMT).

“We don’t want any more demonstrations, we don’t want any more problems in the country. We want to choose for ourselves, by voting,” Alain Randriamandimby, 43, a T-shirt printer, said early in the morning.

Rajoelina, 49, is one of 13 candidates on the ballot, but 10 of the others have called on voters to shun the elections, complaining of an “institutional coup” in favour of the incumbent.

Since early October, the opposition grouping — which includes two former presidents — has led near-daily, largely unauthorised protest marches in the capital.

They have been regularly dispersed by police firing tear gas.

“We appeal to everyone not to vote. Conditions for a transparent presidential election, accepted by all, have not been met,” Roland Ratsiraka, one of the protesting candidates, said on Tuesday.

“We do not want to participate in this fraud, it is a joke on Madagascar.”

On Wednesday, authorities imposed a nighttime curfew in the capital Antananarivo, following what the police prefect said were “various acts of sabotage”.

Rajoelina — who first took power in 2009 on the back of a coup, then skipped the following elections only to make a winning comeback in 2018 — has ploughed ahead despite the tensions.

As his opponents refused to campaign, he flew across the country by private plane, showcasing schools, roads and hospitals built during his tenure.

“It is irresponsible to encourage voters not to vote,” said his campaign spokeswoman Lalatiana Rakotondrazafy, accusing the opposition of wanting to “sabotage” the vote by “attempting to take the entire nation hostage”.

Eleven million people are registered to vote in the country of about 30 million.

– Poverty and anger –

Faced with a wide boycott, a strong turnout will be key for Rajoelina.

Less than 55 percent of those registered showed up for the first round of voting at the last elections in 2018.

For many in the country, politics is not a priority.

“What matters to us is first and foremost getting by on a daily basis,” said Benedicte Lalaoarison, 61, an underwear seller in the Analakely market in central Antananarivo.

At a nearby newsstand, some residents looked concerned as they scanned through newspaper headlines.

“People have become aware of the dictatorship we live under,” said Chrishani Andrianono, 55, complaining that after 11 years in power, Rajoelina had little to show for it.

“We do not see what he did for us.”

The country has been in turmoil since media reports in June revealed Rajoelina had acquired French nationality in 2014.

Under local law, the president should have lost his Madagascan nationality, and with it, the ability to lead the country, his opponents said.

Rajoelina has denied trying to conceal his naturalisation, saying he became French to allow his children to pursue their studies abroad.

His challengers were further enraged by another ruling allowing for an ally of the president to take over the reins of the nation on an interim basis after Rajoelina resigned in line with the constitution to run for re-election.

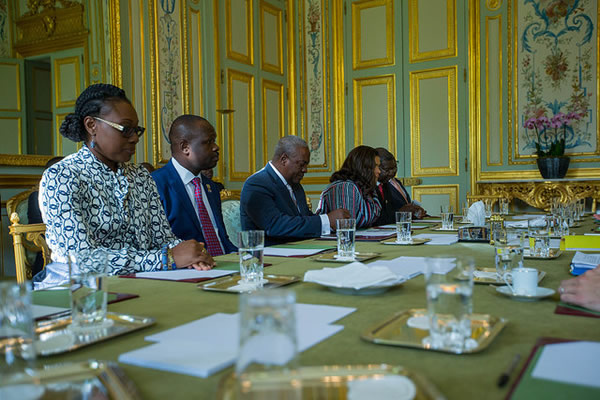

The opposition grouping has led near daily, largely unauthorised protest marches in the capital

They have also complained about electoral irregularities.

Vonjisoa Tovonanahary, a 34-year-old, opposition-leaning Antananarivo resident, said some in his neighbourhood had been promised money to go and vote.

“They want to buy us,” he said with a grimace. “I will follow the instructions and I will not vote.”

The opposition grouping has vowed to continue protesting until a fair election is held.

The Southern African Development Community (SADC), a regional bloc, as well as the African Union and the European Union have sent observer missions to monitor the vote.

Source: africanews.com