There is a well-deserved excitement about the return after six years of political rallies in Tanzania.

Unbanned last month by President Samia Suluhu Hassan – Mr Magufuli’s successor, it has even prompted the return of opposition politician Tundu Lissu from self-imposed exile. He was able to address his ecstatic supporters at a massive rally in Dar es Salaam last week within hours of landing.

Such gatherings are the engine of politics here: the convoy of motorcycle taxis disrupting traffic and businesses on main roads, supporters chanting party songs and later the blaring of loudspeakers as politicians address the crowd. They really give life to local politics.

As Dan Paget, a University of Aberdeen political lecturer with a focus on Tanzania, has said, they are the country’s real form of mass communication.

“Indefinitely banning rallies does to public communication in Tanzania what indefinitely banning television, or the internet, would do in the global north,” he wrote.

They were the way the late president spoke to the country – especially after coming to office in 2015. He roamed freely on the road, making endless stops at villages and towns where he embarrassed and fired unpopular local officials and announced off-script policies.

He wanted the world to believe that he was the hardest-working president the country had ever had.

Yet at the same time he forbade the opposition from exercising their constitutional right to assembly – his administration harassed and even arrested rival politicians when they held internal party meetings.

Magufuli made us believe that he did this to defend his ruling Chama Cha Mapinduzi (CCM) party, saying the opposition were puppets of foreign interests.

But the opposition actually posed no real existential threat. Magufuli just loved power, never missing an opportunity to bully those who did not agree with him – and seeming to delight in the suffering of his opponents.

Banning the rallies effectively cut off the opposition’s political lifeblood. It must have given him ultimate satisfaction.

Many analysts agree that the return of rallies comes down to efforts made by the new president, who has been in negotiations with the opposition Chadema party for a while.

She summed up her mission in a surprise op-ed printed in Tanzanian newspapers last year to mark the country’s 30 years of multiparty politics.

It was, President Samia wrote, to fulfil the four Rs: reconciliation, resiliency, reforms and rebuilding.

Her critics may argue that this is easy to achieve given she has taken over from someone with such a poor record on democracy – also pointing out that she served as Magufuli’s deputy for nearly six years.

Charm underestimated

Yet since taking over in March 2021, President Samia has demonstrated that she does seem to genuinely care about fixing a broken system. She was under no real pressure to change.

In the early days of her presidency, almost any policy change she made or a new direction her administration took was met with dismissive conclusions that she was being controlled by different factions of the CCM.

The legacy of Magufuli’s misogynist leadership style certainly made it difficult for a woman to flex her muscles in what is still a conservative, patriarchal society.

So it has been good to see her handle male egos as she has subtly ushered in change and won battles against her critics such as the parliamentary speaker, who resigned last year.

She has surprised the doubters who underestimated her charm.

In fact such is the respect in which she is now held, a new word has been created for the praise and flattery the president now receives – “chawacracy”, meaning shoe-licking.

And ultimately President Samia has emerged as an ultimate winner of this latest reform.

It is an admission that many Tanzanians, especially those who don’t support the ruling party, do not want to say out loud, but it is only fair to give her the credit she deserves.

Even Chadema leader Freeman Mbowe recently praised her at his party’s first rally on the shores of Lake Victoria: “I don’t have a problem congratulating the chairperson of the ruling party CCM when she saw the need [for reconciliation], accepted it and told me: ‘Honourable Mbowe, let’s move forward.'”

To please the CCM she could have continued with the status quo, but she gambled – and it seems to be paying off.

Interestingly she did it with a sleight of hand – it required no legal reforms, but it also means there is no guarantee that it cannot be reversed.

And the 63-year-old has also demonstrated her control. She is the one who issues the outcomes of the negotiations with the opposition in a manner and at times that suit her the most.

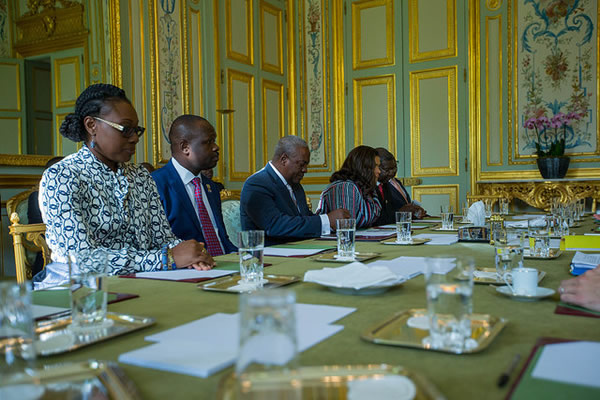

Even the setting of the announcement allowing rallies was telling – it was not a joint press conference in a neutral setting alongside Chadema on an equal footing. Instead it was at state house, pretty much reminding everyone who was in charge – with many smaller, and some would argue insignificant, opposition parties also present.

This new era for the opposition poses daunting challenges. Seven years of effective dictatorship has left many people apathetic about politics here.

Plus their sources of funding have been systematically and significantly crippled.

Opposition parties have only a year to travel around a massive country before important local elections next year, with general elections following in 2025.

Both will serve as litmus test as to how effective rallies can really be.

Source: BBC